Learning the truth in simulation studies

Have you ever done a simulation study where the estimand is not a parameter of your data-generating model? Then read on…

This is my personal prequel to the freshest preprint on arXiv: ‘Revealing the truth: calculating true values in causal inference simulation studies via Gaussian quadrature’1

Background

The abstract of our 2019 tutorial paper on simulation studies says:

A key strength of simulation studies is the ability to understand the behavior of statistical methods because some “truth” (usually some parameter/s of interest) is known from the process of generating the data.

– Morris, White and Crowther (2019)2

Why? Several of the performance measures listed in table 6 involve 𝜃 in the columns for Estimate or Monte Carlo SE. 𝜃 is the true value of the estimand, meaning we can only estimate performance for these measures if we know 𝜃.

Outcome simulation

In section 5.4, we admitted that we don’t always have the privilege of knowing 𝜃. We pointed to what some authors have done, which is to estimate 𝜃 using a very large, independent simulated dataset. This is not ideal: 𝜃 is supposed to be a fixed quantity and by estimating it, we add some Monte Carlo error3. The further our estimate of 𝜃 is from its true value, the worse we will do. Unbiased methods will appear more biased. Coverage will be slightly low, and so on. Further, this approach is only possible if we have a known-unbiased estimator.

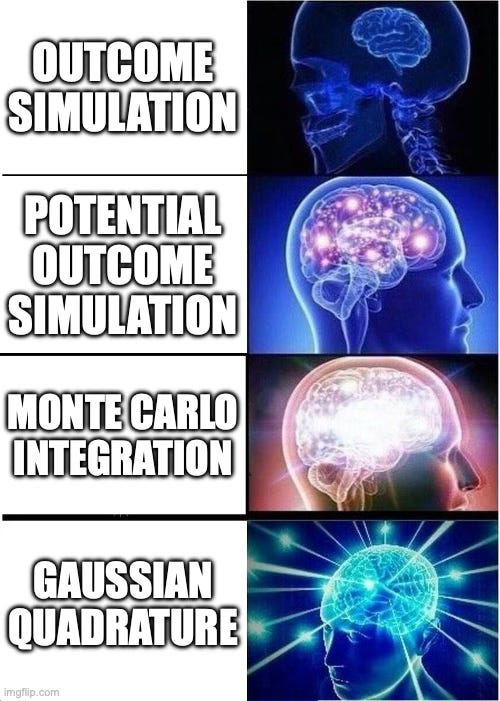

Below, I will outline three other approaches that improve on outcome simulation, and why. In a picture:

Potential outcome simulation

I don’t think anyone has really proposed or used this approach, but it is a reasonable method that’s the obvious stepping stone between two others. Recall the two problems with outcome simulation:

We require a known-unbiased estimator;

It is subject to Monte Carlo error.

Potential outcome simulation does something fairly obvious and simulates all potential outcomes under each action/treatment Z. With two treatments, instead of simulating Y*|Z=z, you simply simulate pairs of potential outcomes (Y⁰*,Y¹*), where the asterisk * represents a draw.

This has two immediate advantages. Firstly, we no longer require an unbiased estimator. A causal estimand is a functional of the marginal distributions of potential outcomes4, so we can simply contrast the required functional. Secondly, we have reduced Monte Carlo error for a given sample size by simulating twice as many outcomes. If you think it’s like doubling the sample size, you’re nearly right. It’s actually even more efficient than that because it conditions on identical covariate values for each row. Though we have reduced it, Monte Carlo error remains.

Monte Carlo integration

Enter Ashley Naimi, David Benkeser and Jacqueline Rudolph with their paper on Monte Carlo integration5. When I read their pre-print I kicked myself for not having come up with this6; which is really testament to how well-written it was!

The idea is similar to potential outcome simulation. However, where potential outcome simulation draws (Y⁰*,Y¹*) pairs, Monte Carlo integration simply fills in the functional of the potential outcomes that defines the estimand. For example, we might fill in (𝔼[Y⁰],𝔼[Y¹]) for each row. Finally, we contrast their distributions to estimate 𝜃. Naimi, Benkeser and Rudolph’s first example involves a normally-distributed confounder, binary treatment, and binary outcome, and they want to learn the true marginal odds ratio. Even in this simple case, we do not automatically know it because the covariate is normally distributed.

Compared with potential outcome simulation, Monte Carlo integration drastically reduces the Monte Carlo error around 𝜃. This is because 𝔼[Yᶻ] – or more generally f(Yᶻ) – is now deterministic (note no asterisk). A small amount of Monte Carlo error remains, however, which comes from the fact that any covariates were simulated. Rather than having their true distribution, we have an empirical approximation thereof. The Monte Carlo error is by now pretty small, but is present.

In early 2025, while still at UCL, I gave a seminar to Novartis about simulation studies, and mentioned Monte Carlo integration and Naimi’s paper. Shortly afterwards, Alex Ocampo (then still at Novartis) emailed me to say that you can actually do better than Monte Carlo integration, and that he and Enrico Giudice (then doing an internship with Alex) had been playing with an approach that has no Monte Carlo error! We got talking, then did a lot of musical chairs with our jobs (me to Novartis, Alex to Roche, Enrico to Novartis) but managed to finish working on a manuscript in December 20257.

Gaussian quadrature

Srsly? You thought I was going to give away the jewel in the crown that easily‽

To find out about Gaussian quadrature, read the preprint! 😜

Postscript

I am currently in mourning. Working on this paper with Alex, Enrico and Zachary was one of the funnest co-author experiences I’ve had; a pleasure throughout. This means I’m a bit deflated we’ve submitted it, rather than relieved… still, there’s always hope – the reviewers may give us a hard time!

Ocampo A, Giudice E, McCaw ZR, Morris TP. Revealing the Truth: Calculating True Values in Causal Inference Simulation Studies via Gaussian Quadrature. arXiv. 2026. https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.05128

Morris TP, White IR, Crowther MJ. Using simulation studies to evaluate statistical methods. Statistics in Medicine. 2019; 38: 2074–2102. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8086

Monte Carlo error is simulation noise. Here, it’s due to the finite sample size of our single simulated dataset. Other times it’s due to a finite number of repetitions.

I’m using the definition from: Hernán MA, Robins JM (2020). Causal Inference: What If. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

Naimi AI, Benkeser D, Rudolph JE. Computing true parameter values in simulation studies using Monte Carlo integration. Epidemiology. 2025; 36(5):690–693. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000001873

I don’t mean Monte Carlo integration, which is well-established; I mean using Monte Carlo integration to learn the true value 𝜃 in simulation studies.

We held off submitting until Jan 2026 because submitting a paper just before Christmas is lawyer timing.

The progression from outcome simulation to Gaussian quadrature feels like watching Monte Carlo error get methodically squeezed out at each step. Potential outcome simulation is an underrated intermediate I hadn't considerd before, the fact that conditioning on identical covariate values makes it even more efficient than just doubling sample size is a neat insight. The musical chairs between UCL, Novartis and Roche during manuscript completion adds a fun real-world twist, curious how much the Gaussian quadrature approach scales when dealing with high-dimensional confounders or non-Gaussian setups.

A comment from Enrico Giudice on this: ‘when you say that “we do not automatically know it [theta] because the covariate is normally distributed”, it reminded me how (surprisingly) complicated it is to get exact results even for non-Gaussian confounders.’ See the appendix of our preprint for more info.